It was the summer 1977. I had just moved into my first flat – a tiny bed-sit, which took up the back reception room of a small terraced house in Tralee. Two elderly sisters lived there (when I say elderly, that’s the perception of my 20-year-old self – they were probably the age I am now!) Their hair was set in iron perms and they wore blue nylon housecoats to spare their clothes. We shared an entrance hallway and a bathroom; they shared an overweening interest in my social life. Under the house rules, gentleman visitors were expressly forbidden. And if you managed to smuggle one in, there wasn’t much hope of anything happening given the monastic single bed, the scanty availability of contraceptives, and, I was sure, the presence of one of the sisters with an ear trumpet to the wall.

I don’t know if the sisters ever got to grips with my erratic schedule – I was a cub reporter with the local newspaper so I kept uneven hours – but since they were creatures of habit, I soon learned their patterns and knew the evenings when the coast was clear. I made the most of it.

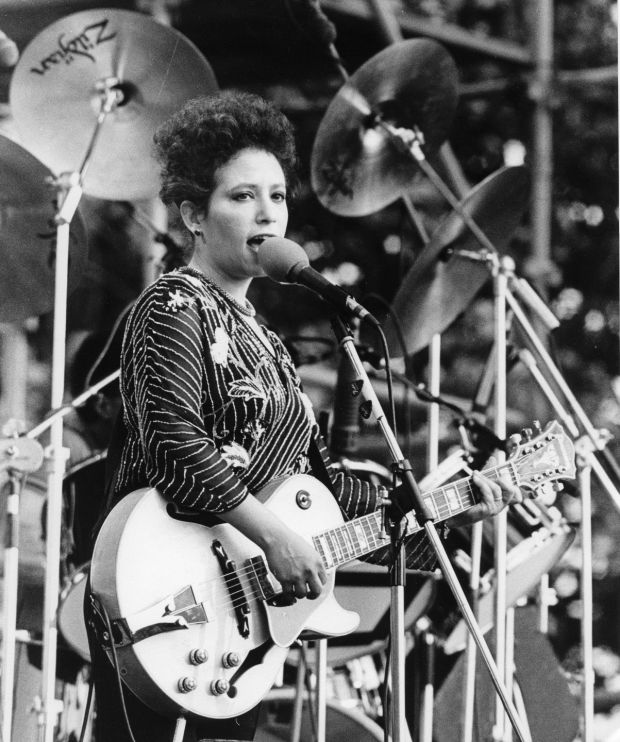

Not that the most was very much – it mainly consisted of playing records at young men. My sound bible of that year was Janis Ian’s “Between the Lines”. Everything about this album spoke to me, the complicated, clever lyrics, its poignant mood, Ian’s soulful, melancholy voice and, it has to be said, its air of romantically grandiose self-pity. That was absolutely fine by me; that was where I was at.

I remember playing the signature track from that album, the Grammy-winning “At Seventeen” to one suitor I was particularly keen on, who blithely dismissed it as juvenile and glib. I was quietly outraged. Little did he know – this was a test and he had failed gloriously. If you didn’t like Janis Ian, I didn’t like you.

What made his verdict more shocking was that very few people of my acquaintance (particularly of the female variety) actively disliked “At Seventeen”. If anything, it attracted too much identification.

It’s a song that voices the feelings of teenage wallflowers, ugly ducklings with acne who are oppressed by popularity politics at school, whose names are “never called when choosing sides at basketball”, who have to invent lovers on the phone to make up for the lack of action in the romance department. Trouble was even tall, thin, blonde, sporty girls who had oodles of boyfriends and no shortage of invitations thought of “At Seventeen” as their song and they would sing mournfully along when it came on the radio.

It was a case of “At Seventeen” – c’est moi .

They seemed to miss the irony that girls like them – the “rich-relationed home town queens who marry into what they need” – were Janis Ian’s target, not her audience.

Over the years, I’ve been a devoted follower of Ian’s – though, I must admit, that for the suitable suitor test, I moved on to “Rumours” by Fleetwood Mac and “Blue” by Joni Mitchell.

Throughout the 70s and into the 80s, however, I bought and savoured and sang along with all of Ian’s oeuvre – “Stars”, “Aftertones”, “Night Rains”, “Restless Eyes” and my own favourite, the concept album “Miracle Row”. Concept album – doesn’t that date both Janis and me! I saw her live twice – once in Vicar Street, Dublin, in the 90s and again in the early Noughties in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where I happened to find myself teaching.

The daughter of radicals – her parents were on a FBI watchlist – Janis Ian was a precocious talent. She wrote her first song at 12 and signed her first recording contract at 13. As a teenager, she partied with Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin – and survived! Both of them, heavily addicted, warned her off drugs and steered her away from dealers. She was friends with Nina Simone and James Baldwin, she did backing vocals for Leonard Cohen and James Brown.

Most people don’t class Ian as a protest singer, but her first album in 1965 (recorded when she was 14) featured “Society’s Child” about an inter-racial teen romance, which was considered so controversial that 22 record companies rejected it, and radio stations in the south of the US banned it from the airwaves. One radio station in Atlanta which included it on its playlist was burned to the ground and Ian was spat at on the street and heckled during performances. But it was championed by composer Leonard Bernstein and became a hit. Ella Fitzgerald dubbed her the “best young singer songwriter in America”.

She’s had two long breaks from recording, one after the breakdown of a violent first marriage, and again in the mid-90s, when she was defrauded by a business manager which meant there was no money for studio time and the proceeds of her live work were going to the IRS. But as she sings in the title track of her latest album, she’s still here.

It’s her first CD in 15 years, and she says it will be her last. Aged 71, she’s on a major tour of the US, after which she’ll devote herself to writing, but there will no more studio albums. For old times’ sake, I bought “The Light at the End of the Line” and although I’d lost track of her after “Breaking the Silence”, her “coming out” album, of 1992, I was delighted to find that although this is is a sparer, harsher sound than those lush, lyrical early albums, she still speaks to me.

This is a voice that has earned its melancholy, its bitter-sweetness and its anger. She hasn’t lost her edge. One of the tracks on the farewell album, “Resist”, a no-holds barred anthemic howl against misogyny, has been roundly boycotted by radio stations across the US for being too “sexual” and she’s been trolled and harangued on social media about it. Plus ca change.

Meanwhile, back in late summer of 1977, while I was quoting lines of hers at the suitors – “love was meant for beauty queens and high school girls with clear-skinned smiles who marry young and then retire,” my permed landladies were hosting a real-live beauty queen. It was the annual Rose of Tralee festival and one of the Rose contestants was staying in the house, chaperoned by one of the sisters. Chaperoning was a hands-on job, requiring strict supervision of the contestant and management of her social and moral diary, assisted by upright young men from good homes who acted as their escorts. (The language of “chaperones” and “escorts” makes it seem more like a Jane Austen novel than a 20th century beauty pageant.)

But the Rose of Tralee organisers were insistent the contest was not just a flesh parade, but a more wholesome enterprise. Inspired by a 19th century parlour song, contestants were required to embody the purity and innocence of the original Rose.

She was lovely and fair as the rose of the summer

Yet, ’twas not her beauty alone that won me

Oh no! ‘Twas the the truth in her eye ever beaming

That made me love Mary, the Rose of Tralee.

Imagine my surprise then when one night coming back to my bed-sit in the early hours, I came upon “our” Rose in the darkened hallway, in full ball gown regalia, creeping up the stairs, stilettos in one hand, leading her escort with the other. I was pretty sure she wasn’t going to be playing records for him.

The landladies were fast asleep; content that their chaperoning duties could be put to bed. I couldn’t believe my luck. Here was a juicy news story right on my doorstep; both the escort and the Rose would be drummed out of the competition for such licentious behaviour. But I suspected, given the importance of the festival to the local economy, that this was a story that might get buried. And I’d certainly get evicted if I spilled the beans about the transgression. So I opted for judicious silence.

There were tactical advantages to keeping it to myself. The secret could be used as ammunition in the future, I thought, if I was ever to be challenged on one of my gentleman callers.