In February it was quietly announced that Warren Plath, brother of the infinitely more famous Sylvia, had died in the US. He was the last surviving family member of Sylvia’s generation. Warren Plath had virtually no presence on the internet and the notice of his death – aged 85 – made no reference to his connection to the internationally known poet. It would be tempting to think this might mark the end of an era though the interest in Sylvia Plath shows no sign of abating, even now 48 years after her death.

For my generation, Plath was one of those writers whose work was handed around like samizdat. Her poetry collections, The Colossus and Ariel, and her novel, The Bell Jar, were staples on our bookshelves . In my early 20s, I devoured Letters Home, her correspondence between 1950-1963, edited by her mother, Aurelia. (It was Plath’s fate to be “edited” by those close to her. Much of the controversy about her legacy centres around her estranged poet husband Ted Hughes’ management of her work after her death by suicide in 1963.)

Plath’s letters had a certain resonance for me. I, too, was the daughter of a widow and recognised the push/pull relationship with her mother when I first read her letters in the early 1980s. (Otto Plath, Sylvia’s father died when she was 8.)

In a widowed family (since widowhood happens not just to the wife) the need for approval is concentrated on the mother. It’s often twinned with an underlying anxiety of what might happen should the remaining parent die. On the other hand, the daugther of a widow learns to withhold worries and tailor expectations – especially financial ones – for fear of overburdening her mother. Signs on, even through much of her inner torments while at Smith College, and later in Cambridge, Sylvia’s letters to Aurelia were determinedly cheery.

Aurelia Plath was ambitious for her children and wanted the very best for them, despite – or perhaps because of – their straitened circumstances. The dynamics of the widow’s family are all too evident in Sylvia’s young letters. She depended utterly on Aurelia, leaned on her for emotional and financial support, wanted to please her, but resented what she called her “hovering”. Her mother gave her conflicting messages – to excel and to conform.

Lest it be forgotten, the widowed mother often longs to be free of her double responsibilities as well. In the 1970s, Aurelia wrote: “I worked to be free of her (Sylvia) & at least live my life – not to be drawn into the complexities & crises of hers.”

After her first suicide attempt in 1953, Plath was given electric shock treatment at McLean, a high-end private hospital in Boston. Her stay there was funded by the author Olive Higgins Prouty, who was a mentor of Sylvia’s, since Aurelia could not have afforded it. (Mrs Prouty paid $2500 over several months to the hospital, a tidy sum at the time. She had not realised Sylvia’s stay would be so long when she first offered help.)

The most recent Plath biography Red Comet; The Short Life and Blazing art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark, drawing on new evidence, suggests that the decision to administer ECT was partly to do with Mrs Prouty’s threat to withdraw financial support. If Sylvia had opted for psychotherapy, for example, her stay at the hospital might have been extended for a year, or more.

Plath’s psychiatrist at McLean, Dr Ruth Beuscher, over-ruled the concerns of medical colleagues at the hospital, claiming that Sylvia’s “over-riding sense of guilt and unworthiness could only be purged by the ‘punishment’ of shock treatments”.

The medical necessity of the treatment seems to have been very far-down the list of priorities.

Ironically, after two of six sessions, Sylvia’s depression began to lift, even though the treatment was then in its infancy. ( Plath had been given ECT at another hospital earlier that summer which had been administered without muscle relaxants or anaesthetic.). She told friends it was like being murdered. She would never forget the effects of it: “I need more than anything. . .someone to love me, to be with me at night when I wake up in shuddering horror and fear of the cement tunnels leading down to the shock room.”

After her death, Ted Hughes claimed the controversial treatment “pervaded everything she said and did”. Nowadays we’d call that PTSD. Little surprise that one of the dominant tropes in The Bell Jar, an autobiographical novel about her experiences at McLean, is the image of the Rosenbergs going to the electric chair in 1953. And the metaphor continued to appear in her work. In a diary entry of June 1958 she described her life thus: “It is as if my life were magically run by two electric currents: joyous positive and despairing negative—whichever is running at the moment dominates my life, floods it.”

Although she was never diagnosed as such, Plath is often referred to in retrospect as manic depressive or bipolar. But in many ways, it was the electric shock treatment that moved her into what Susan Sontag calls “the kingdom of the sick”. It medicalised Plath’s depression, turning it into a “condition”. But a reading of her early journals reveals nothing more than a young woman with a bad case of life.

She was 20 when she made her first suicide attempt, and her diaries from that time show what we might nowadays consider as typical existential angst, replete with the solipsistic striving of a high-achieving perfectionist and the disappointments of an idealistic young adult.

“I can’t deceive myself out of the bare stark realisation that no matter how enthusiastic you are, no matter how sure that character is fate, nothing is real, past or future, when you are alone in your room with the clock ticking loudly into the flash cheerful brilliance of the electric light,” she confided in her journal.

But they also show a woman in a pre-feminist era struggling with her female and her artistic identity. “I’m just not the type who wants a home and children of her own more than anything else in the world. I’m too selfish, maybe, to subordinate myself to one man’s career.”

Even at that stage she was grappling with how to combine being a poet and a woman.

Sylvia Plath was facing those same choices in 1963 when she killed herself. She was a single parent, recently traumatically separated from Hughes, struggling to fend for two small (and at the time sick) children on her own – an unconscious mirror image of her mother? – while in the grip of a severe depression and the worst winter England had endured in decades.

She had an appointment at a psychiatric hospital set for the week following her death so help was at hand. But she was also consumed with dread that she might be forced into electric shock treatment again, something she knew she couldn’t face. It was almost as if the “cure” had become the illness.

However, she had resolved one of those choices. She left behind on her desk the completed manuscript of Ariel, her ground-breaking second collection of poems, which was published two years later to great acclaim and established her as a poet of standing.

As a tyro writer, I admired Sylvia Plath for how much she wrote. Her collected letters have been reissued in two massive volumes in 2017 and 2018, there are her journals and calendars, along with poems and fiction from an early age. She was constantly engaged with her interior life ( perhaps, sometimes, too much) and always observing – images and ideas from her letters turned up in poems, as did passages from her journals. There is no doubt how vividly she lived on the page. This wealth of material has also meant that Plath is a biographer’s dream. The sheer volume of material written about her amounts to a kind of pathology – or is it Plathology?

To which, I suppose, this blog is adding its two cents’ worth.

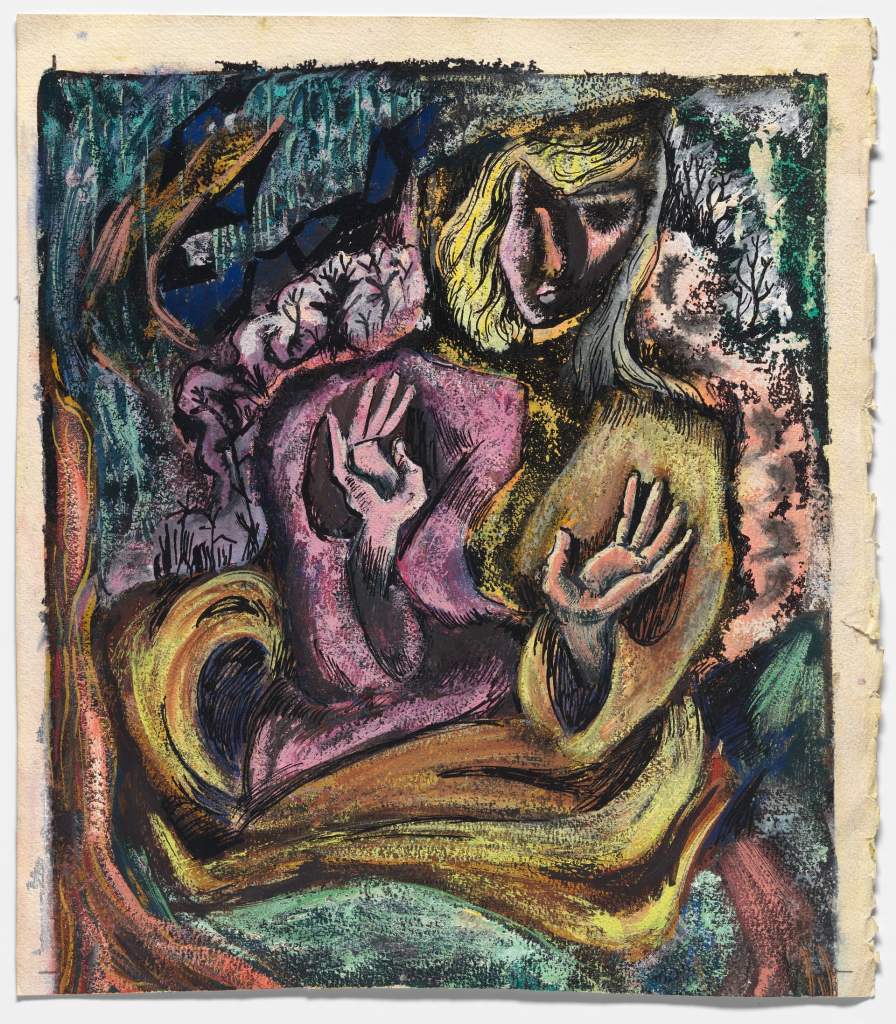

Above: Self-portrait in Semi-Abstract Style by Sylvia Plath, 1946: Estate of Robert Hitter