Works of fiction often have a soundtrack – music you might have listened to while creating them, or popular songs you’ve used to identify the time period of a piece. When writing a story from my recent collection, Twenty-Twenty Vision, on the theme of hindsight, I had to choose a piece of music for one of the stories set in Germany in the late sixties. In the story an unlikely couple – a middle-aged German woman and an Irish teenage boy – end up dancing together to a record in the woman’s living room. She is the mother of the Irish boy’s German pen pal – hence the location. They don’t have a language in common and the dance fills up the dumb, awkward silence between them. So the question was – what music would they dance to?

Immediately, I reached for “Games that Lovers Play” an album of romantic love songs by composer and conductor James Last. It was a sentimental decision, for reasons that will become clear.

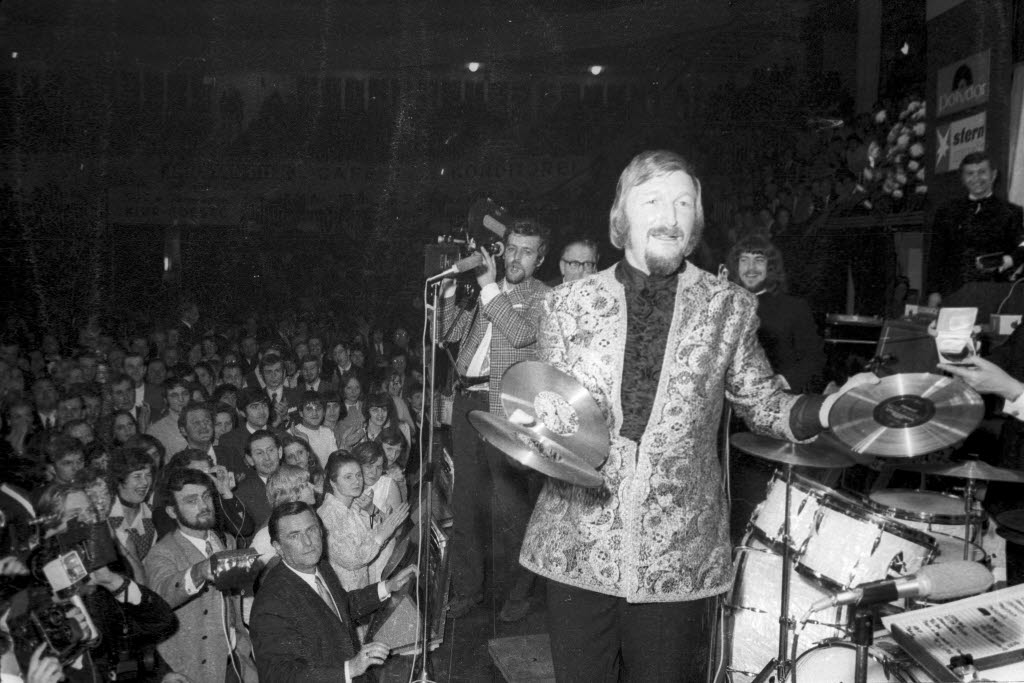

James who, I hear you ask? No longer a household name, but he once was. Think of Andre Rieu but in the Seventies. Last was a German composer and big band leader – see how old-fashioned that sounds – with his own orchestra. He sold an estimated 200 million records worldwide with 65 of his albums reaching the UK pop charts.

He had longevity if not widespread respect in the music world. His final performance was in 2014 at London’s Royal Albert Hall where he had performed 90 times during his lifetime. He was distinctly MOR – his brand was easy listening and he was derided by critics as being the king of elevator musak.

But in 1970, he became my father. I mean, of course, figuratively. This is not a paternity suit in the making. Even if it were, I’d be ten years too late – James Last died in 2015.

While he was making it big, my biological father was trying to educate me into classical music. I was 12 and stumbling through Royal Academy grades on the piano but what he was aiming to impart was a more discerning musical ear. The education was in its early stages and already I sensed that my preference for the lighter, schmaltzier side of the classics – I had a musical crush on the Blue Danube waltz – was probably a disappointment to him.

(To this day, one of my guilty pleasures is to tune into the New Year’s Concert from Vienna where the Blue Danube and that other Strauss standard, The Radetzky March, are always played as an encore accompanied by loud clapping from the highly-coiffed, well-heeled patrons. This year, in a departure from tradition, the first-timer conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic for the new year gig, French-Canadian Yannick Nézet-Ségún, leapt from the stage and patrolled the aisles conducting both orchestra and audience while flaunting a set of powder blue sparkling fingernails during the traditional set-piece.)

My father was an auto-didact where classical music was concerned. Here was a man who had bought Donizetti’s Lucia de Lammermoor not because it appealed to him, but because he felt he should appreciate it and he trained himself to like it by assiduous listening. It was that kind of assiduity and concentrated listening he was trying to instil in me. Although he never quite weaned me off the Blue Danube, we had progressed on to Elgar’s Enigma Variationsand Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave and he was even threatening some opera on me, when he fell gravely ill and died. It seemed the end of the road for my musical education.

Eight months later, there was an LP among my Christmas presents – from my mother. It was James Last’s Classics up to Date Volume 2, which showed on its cover a smooching couple in soft-focus dressed in dinner suit and evening gown. I’m pretty sure there were champagne glasses involved too. My mother knew nothing about classical music and I’ve no idea how she set about choosing James Last for me. Perhaps someone in the record shop had advised her.

My father would have turned in his grave if he’d heard Last’s versions of the music he revered. He’d have cringed at the quickening of the tempos, the driving modern brass and drums section, the plucking guitars, the insidious tickety-tick of the high-hat, and the female humming choruses added to some of the tracks. Listening to it now, I hear only the transgressions, and sense the thinning and flattening effect of all this fussy orchestration.

But then, the 13 tracks in Classics Up to Date, Volume 2, which I played until I had practically worn the vinyl out, formed, for good or ill, the foundation stone on which my musical taste was built. Although I don’t still have the LP – how is it, I wonder, that we let our most treasured sentimental totems slip through our fingers? – some of this music I still love today.

There’s Mendelssohn’s Andante for Violin Concerto in E Minor, Dvorak’s Slavonic Dance no 10, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No 21 in C major, (otherwise known as Elvira Madigan), the Presto from Beethoven’s 7th, Bach’s Ave Maria, Schubert’s Impromptu No 2 in A flat, Borodin’s Prince Igor, and, of course, the piece de resistance – or at least, my piece of least resistance – the Blue Danube waltz.

Each one of these tracks was a portal to further discovery, leading me further into the riches of the real thing. The album marked the resumption of my musical education and for a brief season, James Last stepped in and, however remotely, became my father.

Photograph: James Last being presented with three gold discs at a concert in Kiel in 1970. Photograph Friedrich Magnussen .https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bandleader_James_Last_in_der_Ostseehalle_(Kiel_47.718).jpg