I’ve just done one of those quickie questionnaires on the Irish Times website. I love reading these things but it’s a strange sensation to read your own! And, of course, you get troubled by esprit d’escalier – all the cool and impressive answers you should have given… But the spirit of the exercise is not to think too much about the questions, I think, and not to brood too much about your answers. And , above all, to remember that it’s newspapers, folks; it’ll soon be wrapping up someone’s virtual fish. Or lurking behind a pay wall.

What was the first book to make an impression on you?

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. It was one of many classics read to me when I was very young.

What was your favourite book as a child?

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte.

And what is your favourite book or books now?

Too hard to be definitive about this as favourites keep on changing, don’t they? But I would count Alice Munro as one of my favourite writers and I happily revisit her dozen or so volumes of short stories regularly.

What is your favourite quotation?

“Fail again, fail better” – Samuel Beckett

Who is your favourite fictional character?

Can I say Jane Eyre again?

Who is the most under-rated Irish author?

Eilis Ní Dhuibhne. Her range is amazing. She writes in Irish and English, across several different genres. Her short fiction, in particular, is formally inventive and often wryly funny. The Dancers Dancing, her novel about the Irish college experience, should be a classic.

Which do you prefer – ebooks or the traditional print version?

I read both. I prefer traditional print, as I love the book as object, but am attracted by the ease and lightness of ebooks.

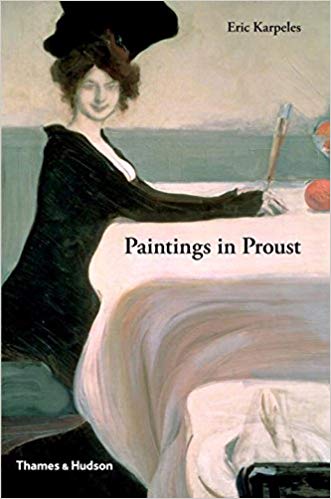

What is the most beautiful book you own?

Paintings in Proust by Erik Karpeles – this is a companion book to Proust’s A La Recherche de Temps Perdu with reproductions of all the art Proust mentions in his text. It’s a beautiful to hold, the reproductions are exquisite, and it’s a fascinating sidelong view of Proust’s masterpiece.

I write at home in a small study that used to be the spare bedroom until I jettisoned the bed and forced guests to sleep on a sofabed in the living room. I do a first draft in long-hand – an old habit which I’m too superstitious to depart from now.

What book changed the way you think about fiction?

The Broken Estate by James Wood. Or anything by James Wood – he’s a literary critic who constantly forces me to re-evaluate reactions to books I’ve read. I don’t always agree with him, but he always makes me think twice.

What is the most research you have done for a book?

Probably for my most recent novel, The Rising of Bella Casey, about Sean O’Casey’s sister. I was awarded a research fellowship at the New York Public Library as I was starting the novel so I was in residence in one of the most extensive libraries in the world. Usually, I write the novel first, then do the research afterwards – but for this novel, the procedure was reversed. I researched Sean O’Casey’s papers (housed in the NYPL), read his letters and the various biographies of him, as well as foraging through testimonies of tenement life, the effects of syphilis, the first World War and the social history of the early 20th century. All of this was at hand and I ended up with more material than I knew what to do with – for that novel and for others yet to be written.

What book influenced you the most?

Again, it’s hard to answer this. As a writer, the books that have influenced me most – though probably subliminally – are the novels I read in my mid-teens, an age when you’re wide open to being carried away. Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor both had that effect on me at that age. I felt I had stumbled on a great secret finding them and I think they hover still around my writing somehow.

What book would you give to a friend’s child on their 18th birthday?

Oh God, I’d probably give them a book token and let them choose. Otherwise I’d give them Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell which I read at 18. I was mesmerised by it because it was about Paris, where I’d never been, and because it was so dark, raw and edgy and a million miles from my own very sheltered existence.

What book do you wish you had read when you were young?

Ulysses by James Joyce

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

Write – a little and often. Read a lot.

What weight do you give reviews?

Enormous if they’re good.

Where do you see the publishing industry going?

If I knew the answer to that. . .

What writing trends have struck you lately?

The predominance of present-tense narratives in short fiction and the large number of polyphonic novels.

What lessons have you learned about life from reading?

I don’t look to reading to teach me about life; I use it to escape life.

What has being a writer taught you?

Dogged persistence.

Which writers, living or dead, would you invite to your dream dinner party?

I would like to invite the residents of The February House, a literary commune set up in Brooklyn in the early 40s, which counted among its many members Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten, W H Auden, George Davis, Paul and Jane Bowles, Gypsy Rose Lee, Klaus and Erika Mann, along with a host of famous visitors, including Anais Nin and Louis Mc Neice. Rather than be the host of the dinner party, I’d like to be a fly on the wall during one of their gatherings.

Brought to Book: Mary Morrissy on Alice Munro, Jane Eyre and James Wood.