In my recently published novel, Penelope Unbound, which splits James Joyce up from his wife, Norah Barnacle, and gives both of them an imagined life apart, I had to indulge in some literary matchmaking. My first task was to find a new wife for Joyce. I paired him off with Amalia Popper (see blog of October 10) a young woman he’d taught in Trieste, and for whom he held a romantic torch. His poetic fragment about unrequited love, Giacomo Joyce, was supposedly inspired by Amalia.

But that was only one half of the story. I also had to find a new romantic partner for Norah Barnacle. Somehow, I couldn’t imagine she’d be alone for long.

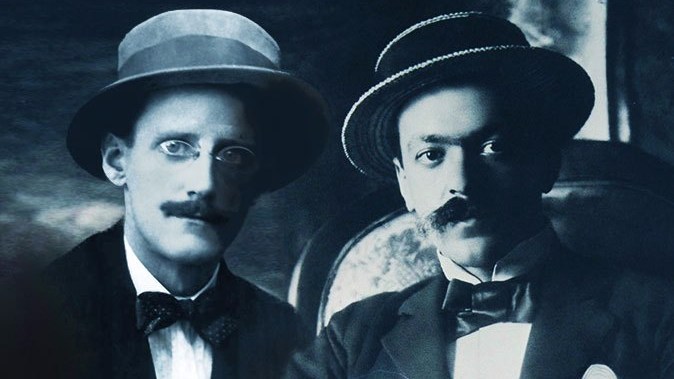

One of the fictional contenders for her hand was the Italian modernist writer and reluctant businessman, Italo Svevo, who, in real life, was a friend of Joyce’s (pictured together above). He came to Joyce for English lessons in Trieste in 1907. As the friendship developed, Svevo (a pen-name ; his real name was Ettore Schmitz) admitted to Joyce his own literary ambitions.

He’d written and self-published two novels, Una Vita (1893) and Senilità (1898), which had sunk without trace . The ignominy of this, and his burgeoning career as a businessman working for his wife’s paint manufacturing business, led to his abandoning his writing.

When Joyce read Svevo’s ignored early work, he proclaimed him a fine novelist, the equal of Anatole France. But he was too obscure a writer himself to be able to do much to aid his pupil’s literary efforts.

For his part, Svevo provided Joyce with lots of material for Ulysses. As Joycean scholar Terence Killeen notes, much of what Joyce wrote about Leopold Bloom’s Jewish background came from Svevo. “On the most basic level Joyce derived information about Jewish customs and perceptions from Schmitz (Svevo); he constantly bombarded the unusual Triestine businessman with queries about such matters. Schmitz, though he was not even formally a Jew by this stage, had experienced enough of that world as a child and a young man to be able to pass on a great deal of knowledge.

“There is also good reason to believe that elements of Bloom’s character derived from Schmitz. Bloom’s diffidence, his not entirely thoroughgoing cynicism, his gentleness, his reasonableness, the breadth of his sympathies, all seem to be characteristics that Schmitz shared.”

(Joyce also borrowed Svevo’s wife’s name, Livia, and her hair, for the Anna Livia of Finnegans Wake.)

However, after a gap of 25 years – described as “one of the longest sulks in literary history” – Svevo returned to writing and produced his masterpiece, La Coscienza di Zeno, (The Conscience of Zeno) in 1923 when he turned to Joyce again. This time, Joyce, living in Paris as a celebrated author after the publication of Ulysses, was much better placed to be of assistance. He helped to get Zeno published and turned the book into a literary success.

The Conscience of Zeno purports to be the journal of a man undergoing psychoanalysis, written at the behest of the analyst, and then published by the analyst to avenge the patient’s termination of his treatment.

Zeno Cosini, a Trieste businessman now in his late fifties, is a “hypochondriacal, neurotic, delightful, solipsistic, self-examining and self-serving bourgeois, a true blossom of the mal du siècle,” writes critic James Wood. ”The novel we are reading is supposed to constitute his memories.”

Zeno recalls his attempts to give up smoking as well as his farcical attempts to find a wife. He goes through the four Malfenti sisters but ends up marrying the one he at first found the ugliest. He also describes his forays in business – Zeno is a terrible businessman who accidentally does very well.

“The entire novel must be read in the light of the comic paradox whereby Zeno thinks he is analysing himself while at the same time being certain that psychoanalysis lacks the means to analyse him. And given this paradox, what are his confessions for? ” writes Wood.

The novel, one of the first to challenge and mock psychoanalysis in the early 20th century, was an enormous success, thanks in no small part to Joyce’s promotion of it. Though perhaps not well known here, The Conscience of Zeno is considered a masterpiece of Italian modernism.

But that’s just mere real life.

None of this happens in Penelope Unbound. Instead, Norah and Jim get parted; Joyce never meets Svevo. And it’s Norah Barnacle whom Svevo befriends. She ends up working in the Svevo household, first as a servant then as a governess to Svevo’s daughter Laetitia.

And then? Well, you’ll have to read the book to find out.

The Conscience of Zeno was published 100 years ago this year; Italo Svevo was born on this day in 1861.

Photographs: (Top) James Joyce and Italo Svevo. (Below right): Norah Barnacle, a1926 portrait by American photographer Berenice Abbott.